The starting situation

Several companies rate and sell carbon credits. Most often, these credits are generated by preventing deforestation. Owners of threatened forests create credits by protecting them, claiming that extra carbon is absorbed by trees that would otherwise be cut down. Certifiers like Verra or Pachama rate and market these projects. However, this can become a problem, for example, when certifiers are selling credits generated from forests under no threat at all.

Carbon offsetting: how it works in more detail

A carbon credit is created by a project developer for activities that should result, in theory, in a benefit to the climate. This project developer could be a private company or a conservation group. Each credit is designed to account for one tonne of carbon being removed from the atmosphere, or one tonne fewer being emitted.

Most projects involve protecting a stretch of forest that the developer says is under threat. By preventing trees from being chopped down, the developer ensures more carbon is absorbed.

When a project is considered worthwhile, auditors hired by the developer check the project, following a pre-defined methodology, often involving a hypothetical “baseline scenario” which the actual outcome of the project is measured against. If auditors give the project a green light, it is then approved by a certifier, which issues the project with carbon credits and allows the project to register on its database. Once listed on the database, credits can be bought by companies like BA, Lufthansa, or Shell, wishing to offset carbon emissions and use them to claim that people can fly or drive “carbon-neutral”.

Which indeed sounds great. Without requiring any major behavioral change, and at a tiny cost to the consumer, the problem of climate change is solved. Having handed over a few Euros or Dollars, we can all sleep easy again. Which of course, sounds too good to be true.

The old controversy about offsets (and our 50 cents)

It has long been disputed if offsetting is helpful at all, irrelevant – or even counterproductive in the fight against climate change. It has famously been compared with the ancient Catholic church’s practice of selling indulgences. And while some experts argue that carbon offsets can help achieve emissions goals, others say they are actively dangerous. The latter argue that from a climate perspective, offsets are worse than doing nothing, e.g., because of the “rebound” effect.

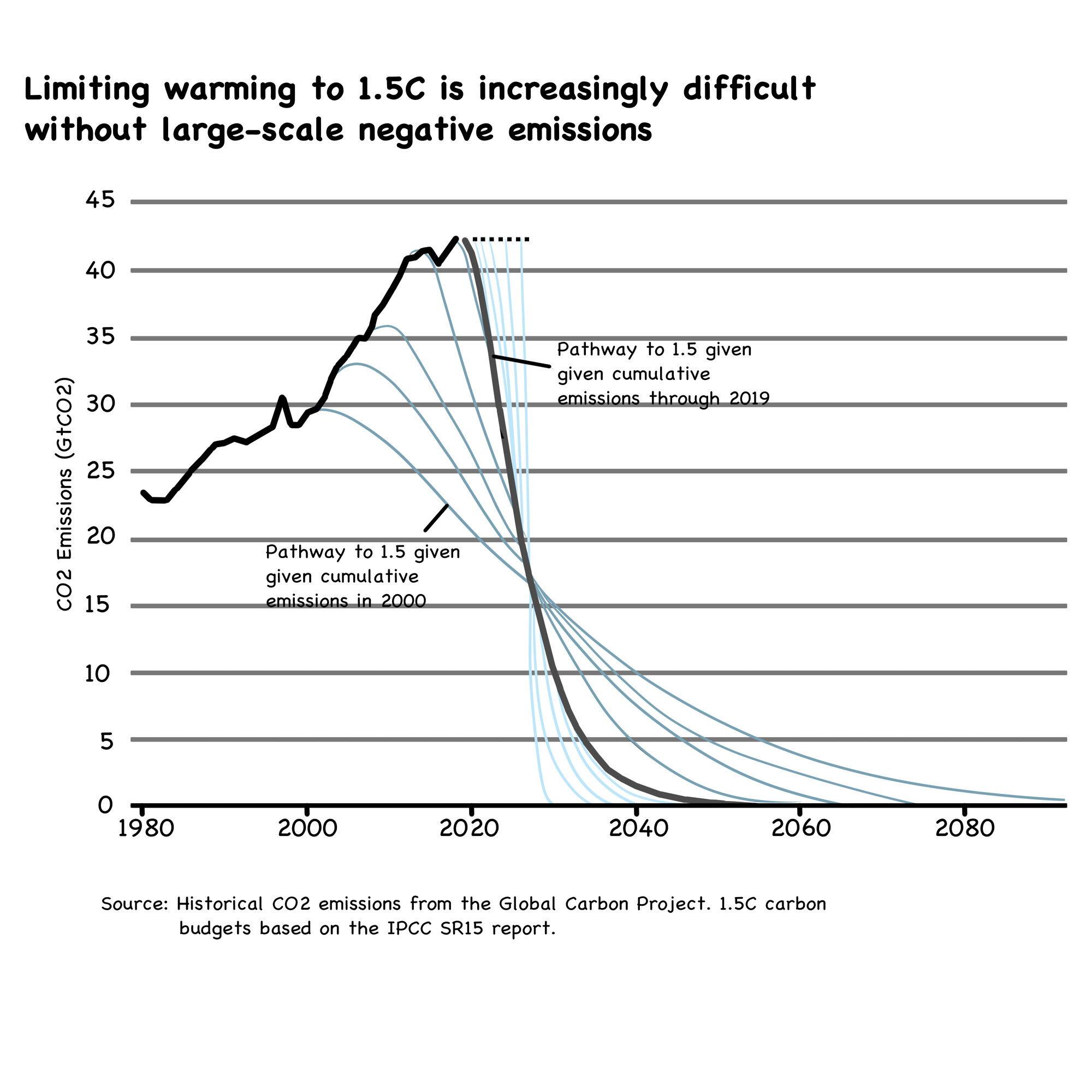

Both lines of argumentation have merits. We believe that offsetting can be dangerous and its positive impact is overrated – but we are also in a bad climate emergency. So we will just have to work with offsets, without which we have even fewer chances to halt global warming between 1.5 and 2.0 degrees.

In theory, “good offsets” could be helpful in our fight against climate change – but only for companies already cutting their carbon emissions significantly before offsetting. Offsets should be the “extra mile” beyond reductions, but should not be used as a substitute for stringent emission-reduction requirements. In addition, the quality of carbon credits and offsets in the “voluntary market” is somewhat uneven, mildly put. In the last decades, we have seen projects sold that never existed, forests that were actually being cut down, and trees that had died or were being counted twice or several times over. We strongly believe that more standardization of high-quality credits is required.

The findings from the latest studies on carbon certifiers

A recent analysis conducted on the quality of carbon credits seems to support this general view. A study conducted by SourceMaterial, The Guardian, and Die Zeit suggests that of nearly 100 million carbon credits analyzed only a fraction resulted in real emissions reductions. This is very serious – and raises very tough questions for the organizations that many of the world’s biggest companies, and the consumers who buy their products, rely on, to set the standard for effective carbon offsetting—in particular the biggest of them, Verra.

Regarding Verra, the investigation found that only a handful of Verra’s rainforest projects showed evidence of actual deforestation reductions. The authors of the studies indicate that 94% of the credits had no benefit to the climate. The threat to forests had been overstated by about 400% on average for Verra projects, according to the University of Cambridge.

To assess the credits, a team of journalists analyzed the findings of three scientific studies that used satellite images to check the results of a number of forest offset projects. Two groups of scientists looked at a total of about two-thirds of 87 Verra-approved active projects. A number were left out by the researchers when they felt there was not enough information available to fairly assess them. The two studies found that just eight out of 29 Verra-approved projects where further analysis was possible showed evidence of meaningful reduction of deforestation. The journalists further pursued analysis of those projects, comparing the estimates made by the offsetting projects with the results obtained by the scientists. The analysis indicated that:

- About 94% of the credits the projects produced should not have been approved

- Credits from 21 projects had no climate benefit

- Seven had between 98% and 52% fewer than claimed

- Only one had 80% more impact, the investigation found

The journalists again analyzed these results more closely and found that, in 32 projects where it was possible to compare Verra’s claims with the study finding, baseline scenarios of forest loss appeared to be overstated by about 400%. 3 projects had actuallly achieved excellent results and a significant impact on the figures. However, without those projects, the average inflation would have been even higher at 950%.

Conclusion?

To be fair, Verra does not concur (link). Verra argues that the conclusions reached by the studies are incorrect, and questions their methodology. And they point out that their work has since allowed billions of dollars to be channeled to the vital work of preserving forests.

More analysis is required to support or counter the claims of the studies. Of course, Verra and the studies used different methods, and no modeling approach is ever perfect. However, the data shown by the studies conducted by SourceMaterial, The Guardian, and Die Zeit seems consistent and shows a broad lack of effectiveness of the projects compared with the Verra-approved predictions. Insofar, it may become worthwhile to pinpoint the apparent overstatements of companies who are buying Verras offsets and which have misleadingly overstated how much they are doing to reduce their carbon footprint and how much they are spending on renewable energies.